In sport and exercise, we are often inundated by new trends and fads, many times because people are looking for the quick fix. The secret formula in sport will never be a quick fix. Success is a long process of continuous hard work. It’s about applying the training principles day in and day out and working towards a common goal. The training principles are however often over-looked because they aren’t trendy.

Co-vid 19 has posed many challenges in the way we live and the way we train our athletes. One principle that will be exposed once we return to sport is that of Reversibility. Reversibility can be described as “the observation that withdrawal of tissue loading results in a loss of beneficial fitness and performance adaptation” (Korey, 2019). Assuming all the fitness levels are equal, the athletes and teams that avoid reversibility the most will be at a physical advantage.

We often see these natural cycles in the off-season. Once athletes return from their off season, we utilise other principles such as overload and specificity to graduate them to high levels of conditioning before they play competitive sport. However, that occurs systematically with a definite end goal in sight. We now find ourselves in an unprecedented time without any clarity on how sport will return, so how do you plan?

Reversibility of different physical qualities is paramount to understand. The research suggests that aerobic function will decay first. Aerobic capacity markers will start to demonstrate significant detraining effects within 2 to 3 weeks of training cessation (Mujika, I. & Padilla, S., 2000) ranging from a 4% to 25% drop off in that time (Bosquet, Laurent & Mujika, I., 2012). In addition, muscle fibre distribution remains unchanged during the initial weeks of inactivity. Strength performances and force production declines at a slower rate with significant declines noticed in about 4 weeks of training cessation. However, highly trained athletes’ eccentric force and sport-specific power may suffer significant declines prior to 4 weeks (Mujika, I. & Padilla, S., 2000).

These finding are relatively consistent throughout the literature, however there are limitations to these studies and I’m not convinced they can be extrapolated with huge confidence to be applied to the elite. The authors suggested that there were differences in the pattern of decline across different cohorts. My approach has been to assess, assess and keep assessing. The data I have on the athletes I work with, allows me to monitor them consistently and ensure there is as little drop off as possible across many metrics. this is anecdotal but, in my opinion, it can often tell you more about how the individual responds than the research can. It is my observation that the weaknesses of the individual will become more of a weakness in training reversible patterns. Let me be clear, the athletes who are at their peak will naturally drop quickly as it’s their peak. If an athlete is aerobically proficient, they will maintain their threshold for longer after an initial decay period. Whereas those who are not will lose their training adaptions further.

Of course, genetics and previous training history play a huge role in how an athlete will respond to de-training. The research in this area is limited. Effectively to get further research in elite populations, you would have to let an elite athlete detrain and measure how poor he or she is getting with time. This isn’t something many athletes would sign up for.

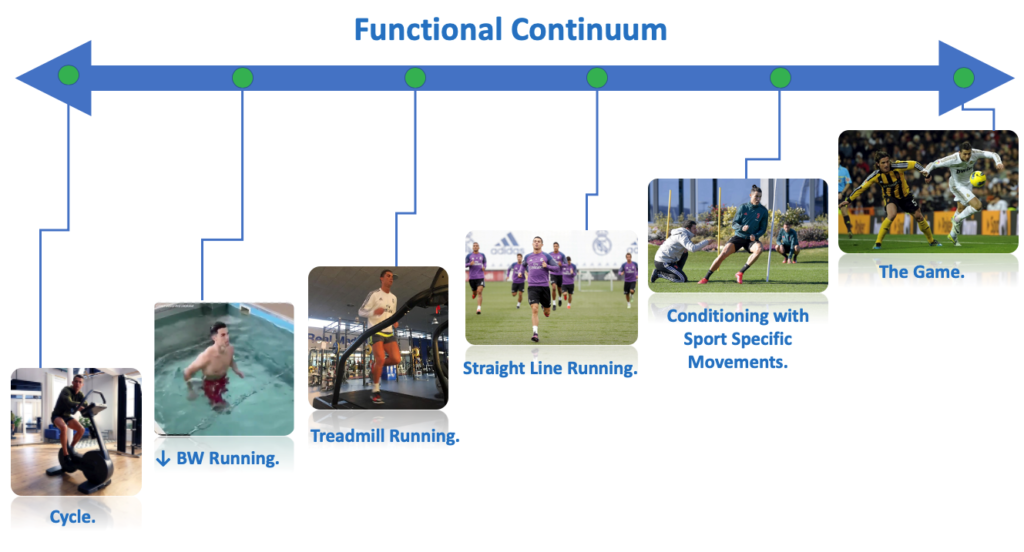

To avoid reversibility, it is my recommendation that we prioritise weaknesses, meaning it should be the main aim but not the only aim. Maintenance of their “strongest physical quality” can be addressed well with maintenance dosages. Once you have established their priority, it’s important to remain as close to their sport as possible. Redpill training express training methods and modalities on a functional continuum – some fit close to the sport and will transfer to performance while others are very far removed. Below is an example of different conditioning methods for football. Of course, there are times when different methods are needed but some have greater transfer than others. There are many facets to this of course and it’s beyond the scope of this discussion but the same applies for exercise selection.

Functional Continuum

The more exercises we select that are close to the sport and that address weakness, the less reversibility we will experience. For example, if I was programming for a footballer and the development area was lower body strength (strength being his weakness, football being the sport), choosing a walking lunge over an isometric wall squat would have more transfer to football thus more transfer to performance. There are many reasons why this is the case – bone rotations, muscle firing patterns, inertia, momentum etc, I will hopefully address this further in a later blog

My 3 take home points would be:

- Ensure the athletes are prioritising weaknesses (without neglecting strengths). The weakness if not addressed will decay further.

- Ensure their conditioning programmes are as close to the sport as possible. For example, with speed drills, adding jockeying movements prior to the sprint will have greater transfer for central defenders.

- When developing power, choose exercises that will gain the adaptation but also the transfer to the sport. For example, plyometric drills that have lateral movements would be more beneficial to goalkeepers than a sagittal dominate programme.

Learn more about the courses available at Setanta College here, or contact a member of our team below.

Contact form

References

Korey, K (2019), Sports Training Principles, Current Sports Medicine Reports, 18 (4) pp. 95-96.

Mujika, I. & Padilla, S. (2000) Muscular characteristics of detraining in humans, Medicine & Science in sports and exercise, 0195-9131 (01) pp. 3308-1297.

Bosquet, Laurent & Mujika, I. (2012). Detraining.

Leave A Comment